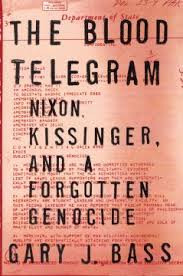

Για τις αδικαιολόγητες σκοτεινές πράξεις στην Ινδία ( και όχι μόνο)του εν ζωή ακόμα 90χρονο σήμερα Henry A. Kissinger Κίσινγκερ , γράφει λεπτομερώς ο Gary J. Bass ,καθηγητής διεθνών σχέσεων στο Πανεπιστήμιο του Πρίνστον και συγγραφέας του “The Blood Telegram:Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide“

Για τις αδικαιολόγητες σκοτεινές πράξεις στην Ινδία ( και όχι μόνο)του εν ζωή ακόμα 90χρονο σήμερα Henry A. Kissinger Κίσινγκερ , γράφει λεπτομερώς ο Gary J. Bass ,καθηγητής διεθνών σχέσεων στο Πανεπιστήμιο του Πρίνστον και συγγραφέας του “The Blood Telegram:Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide“

Can we please stop already with the tributes to Henry Kissinger? As more and more material gets declassified, there are periodic exposures of his uglier deeds.

Walter Isaacson’s biography showed in detail how Kissinger had the FBI put wiretaps on journalists and government officials, including some of his own top staffers.

A couple of years ago, it was revealed that back in 1975, while discussing how the Khmer Rouge had killed tens of thousands, he told Thailand’s foreign minister, “You should also tell the Cambodians”—the Khmer Rouge—“that we will be friends with them. They are murderous thugs, but we won’t let that stand in our way.” More recently, an Oval Office tape was released that captured Kissinger in 1973 saying, “if they put Jews into gas chambers in the Soviet Union, it is not an American concern. Maybe a humanitarian concern.”

And yet Kissinger continues to be publicly lionized in some circles. After his remarkably successful decades-long marketing campaign, he can still call upon an impressive array of friends and cronies to promote him, give him fancy awards or explicitly exonerate him in the press. Last June, at his gala black-tie 90th birthday party at the St. Regis Hotel in New York, the guests included Bill Clinton, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, Condoleezza Rice, Donald Rumsfeld, Barbara Walters, Tina Brown and hundreds more. Secretary of State John Kerry hailed him as an “indispensable statesman,” while Senator John McCain told a reporter, “I know of no individual who is more respected in the world than Henry Kissinger.”

Just this week, Kissinger will be speaking at the Center for the National Interest (CNI), a Washington think tank dedicated to realism and therefore regular encomiums to its most famous practitioner. Once again, he is more likely to be acclaimed than to face serious questions about, for instance, the 1972 “Christmas bombing” of Hanoi and Haiphong or the civilian death toll from the massive bombing of Cambodia.

***

Of all the incidents in Kissinger’s dark past, one of the least defensible must be his and President Richard Nixon’s staunch support of Pakistan’s military dictatorship while it carried out a bloody crackdown on its restive Bengali population in 1971. As Nixon’s national security adviser, Kissinger stood behind Pakistan—a Cold War ally that prized its close military and diplomatic relationship with the United States—even as it swept away the results of a democratic election, killed horrific numbers of Bengalis and targeted the Hindu minority among Bengalis. He reserved his vitriol for India. And he trashed the career of Archer Blood, the brave U.S. consul general in Dhaka who, while witnessing and documenting the onslaught against the Bengalis, dissented from the White House’s pro-Pakistan policy. Here is a case where you’d think that even Kissinger’s most ardent defenders might settle for an embarrassed silence.

Not so. Confronted with the facts in my new book, The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide, Robert D. Blackwill makes a plea for sympathy—not for the hundreds of thousands of Bengalis killed, nor for the 10 million refugees or the traumatized survivors, but for “those at the top of the U.S. government who have to make momentous decisions.” In an expanded essay in The National Interest (which is published by CNI and whose honorary chairman is Kissinger), Blackwill goes further: “We should be grateful” to Nixon and Kissinger for their actions.

ExecutiveOfficeBuilding

In December 1971, Pakistan and India fought a short but decisive war that would result in the creation of Bangladesh. With Pakistan on the brink of defeat, Kissinger proposed to help Pakistan by deploying a U.S. aircraft carrier group to threaten India, secretly asking China to mass its troops on the Indian border, and illegally allowing Iran and Jordan to send squadrons of U.S.-made warplanes to Pakistan. On Dec. 8—a day after receiving warnings from State Department and Pentagon lawyers that it would be illegal to allow the transfer of the Jordanian and Iranian planes—Nixon and Kissinger, joined by John Mitchell, the attorney general, met in the president’s hideaway office in the Executive Office Building and decided to go ahead.

Nixon : … What I mean is let’s do the carrier thing. Let’s get assurances to the Jordanians. Let’s send a message to the Chinese. Let’s send a message to the Russians. And I would tell the people in the State Department not a goddamn thing they don’t need to know. Right, John?

Mitchell: I would hope so.

Kissinger : Except that they have to know of the movement of the Jordanian planes. And I would rather—

Mitchell: Well, you’ve got to give them the party line on that or all a sudden the secretary of state will say that’s illegal.

Kissinger : I’d rather just have—

Nixon : All right.

Kissinger : Let Johnson [presumably U. Alexis Johnson, under secretary of state for political affairs] in on it now.

Nixon : All right.

Kissinger : To say that if they move them against our law, they are not to have [unclear—sanctions?].

Nixon : That’s right.

Kissinger : I mean, I’ve got to tell them that much.

Nixon : All right, that’s an order. You’re goddamn right.

Kissinger : OK.

Nixon : Is it really so much against our law?

Kissinger : What’s against our law is not what they do, but our giving them permission.

Nixon : Henry, we give the permission privately.

Kissinger : That’s right.

Nixon : Hell, we’ve done worse.

These apologetics make a revealing case study in how Kissinger’s reputation stays afloat. Rather than grappling with Nixon’s racist contempt for Indians, or Kissinger’s ignorance about South Asia or emotional misjudgments, Blackwill’s ahistorical piece rests on the careful skewing of the record.

When Kissinger’s actions get too indefensible, Blackwill simply ignores them. Take Nixon and Kissinger’s illegal arms transfers to Pakistan during its December 1971 war against India, where Blackwill goes to considerable lengths to overlook what Nixon and Kissinger knew full well: that they were breaking U.S. law. “Is it really so much against our law?” Nixon asked Kissinger, who admitted that it was. Blackwill ignores such evidence from the White House tapes, as well as the warnings of White House staffers and State Department and Pentagon lawyers that such arms transfers were violations of U.S. law. Instead, trying to change the subject, he writes, “Bass expresses indignation at this proposal, suggesting that it was undertaken to assist in the repression of civilians in East Pakistan”—even though these pages in my book actually concentrate on how Nixon and Kissinger broke the law. Blackwill can’t defend Kissinger for breaking U.S. law, but he can’t criticize Kissinger either, so he just pretends it never happened.

Blackwill’s method throughout is to avert his gaze from the most important evidence at the highest levels, particularly the White House tapes of Nixon and Kissinger’s most unguarded conversations, and stare selectively instead at a small portion of the less revealing stuff: Kissinger’s self-serving memoirs and books, public declarations, big interagency meetings, mid-level statements. This gives a systematic slant to Blackwill’s reading of events, which unsurprisingly validates his own ideological predilections. Anyone wanting the complete story can check out more than 2,600 footnotes in my book (the product of almost four years of comprehensive research in U.S. and Indian archives, untold thousands of declassified pages, and unheard White House tapes), rather than Blackwill’s slipshod little sketch. His real problem is that The Blood Telegram painstakingly documents Nixon and Kissinger’s whole record and draws measured and reasoned conclusions that don’t flatter Kissinger.

While Blackwill—a former senior George W. Bush administration official who is now, aptly enough, the Henry A. Kissinger senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations—wants to believe that Nixon and Kissinger were masters of clear-eyed realpolitik, the White House tapes demonstrate that they were all too often driven by emotion and bias. Don’t take my word for it: At the time, Nixon called Kissinger “emotional” and wondered if he needed psychiatric care; Nixon’s chief of staff H. R. Haldeman saw him as “overexcited” and “overdepressed about his failures”; George H. W. Bush, then the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, found him “very excitable, very emotional almost” and “paranoid.”

Blackwill sidesteps my book’s abundant evidence of Oval Office passion and bigotry only by raising the non-issue of profanity, pretending that I am “curiously offended that conversations in the Oval Office are often not the stuff of a church social.” In fact, the candid quotes from Nixon and Kissinger are salient because they are cruel, racist or reckless, not because they are PG-13. (I even point out that Kissinger didn’t swear much, tending toward “balderdash” or “poppycock.”) Indeed, some of Nixon’s harshest utterances about Indians use perfectly printable language: “I don’t know why the hell anybody would reproduce in that damn country but they do.” Kissinger joked about the massacre of Bengali Hindus, and, his voice dripping with contempt, sneered at Americans who “bleed” for “the dying Bengalis.” Is Blackwill really untroubled by such statements?

http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/01/indefensible-kissinger-102123.html#ixzz2qjA7GIXK